Two weeks after Czechia’s parliamentary elections delivered a decisive win for Andrej Babiš’ ANO (“Yes”) party, coalition negotiations are revealing how uncertain the country’s political future remains.

The vote drew nearly 5.6 million Czechs, the third-highest turnout in the country’s history, signalling both strong civic engagement and deep frustration with the outgoing government. Many voters cited rising living costs, immigration pressures and fatigue with the ruling SPOLU (“Together”) coalition as key reasons for turning out.

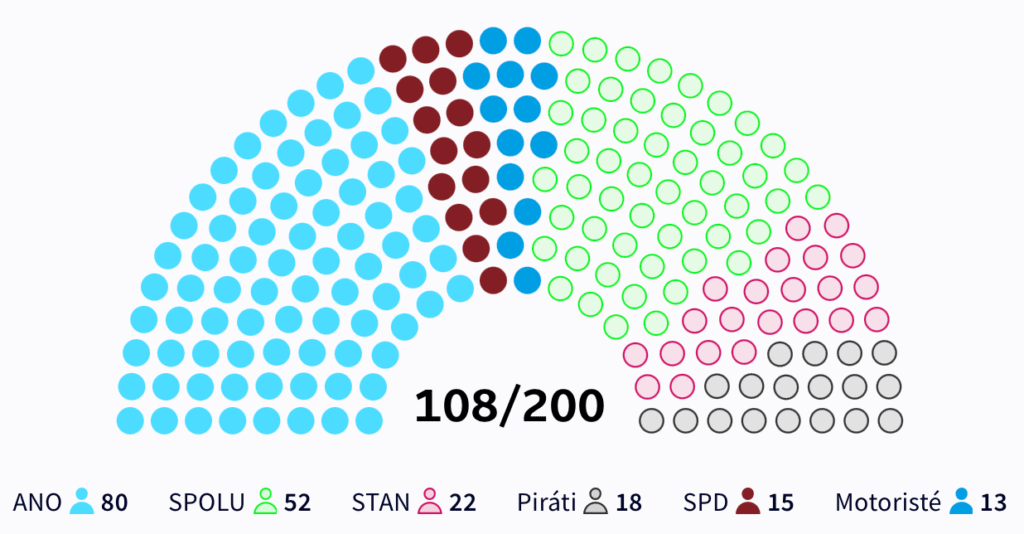

After narrowly losing power in 2021, ANO returned to the top with an 11-point lead, winning a slim majority of 80 out of 200 seats in the Chamber of Deputies.

Babiš initially said he hoped to form a one-party government, but he has since told President Petr Pavel he will seek to build a coalition with the far-right Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD) and the Motoristé sobě (“Motorists Unite”) movement. Together, the three would hold 108 seats, enough for a narrow governing majority.

While Babiš insists Czechia will remain in the European Union and NATO, both potential coalition partners have advocated for a referendum on EU membership.

SPD and Motoristé sobě drew much of their support from regions heavily affected by the influx of Ukrainian refugees, such as Prague and the Central Bohemian Region, where job competition has increased. Support for both fringe far-right parties, however, was scattered throughout the country.

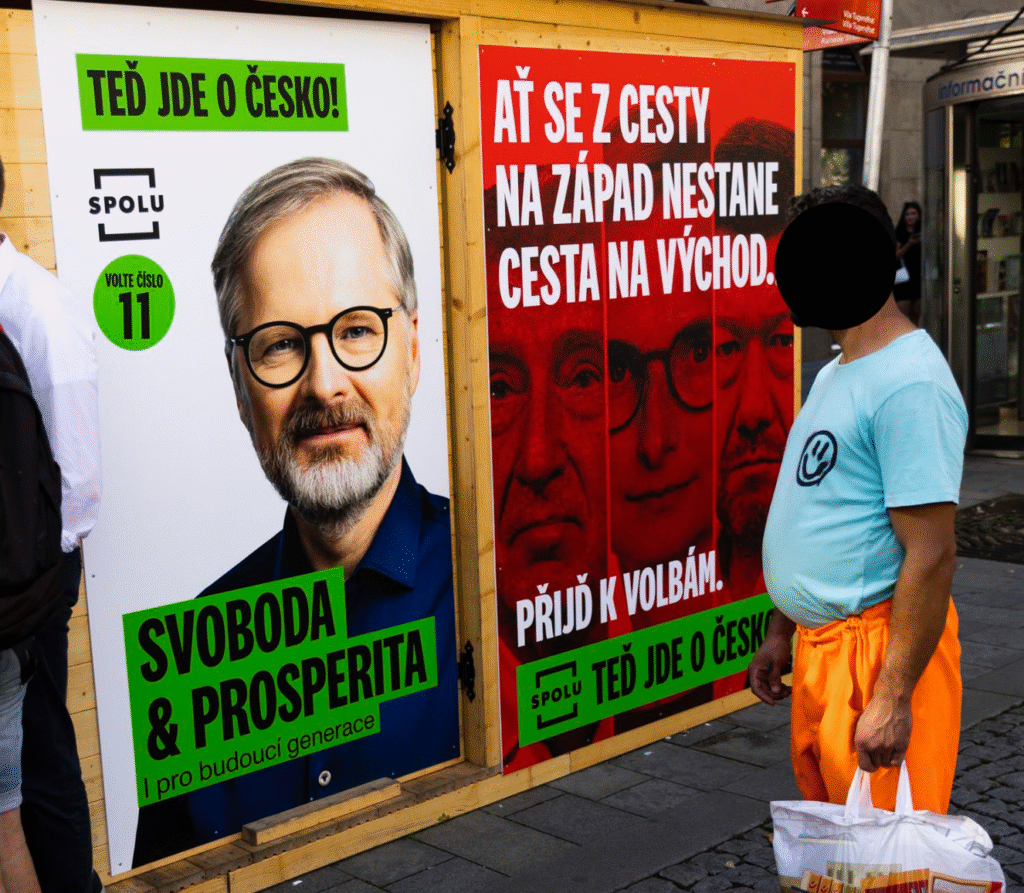

The SPOLU coalition has been left weakened. Its campaign faltered after a cryptocurrency scandal involving a convicted drug trafficker’s bitcoin donation to the Ministry of Justice, which SPOLU oversees. The controversy, combined with the soaring cost of living, overshadowed its message of stability and pro-Western values.

Slogans such as “So communists don’t control us again” and “Vote Freedom! Vote Safety!” failed to resonate with voters more concerned about inflation than geopolitical messaging.

Other centrist and left-leaning parties fared little better. STAN (Mayors and Independents) lost seats, while the Piráti (“Pirates”) party improved its showing, winning 18 seats compared to three last term. SPD lost ground, securing 13.

ANO’s campaign, by contrast, featured slogans like “Vote lower taxes” and “Czech Republic first,” which appeared across billboards and bus stops.

Analysts say the high voter turnout reflected both engagement and protest, particularly among older voters who make up a large share of the electorate and were drawn to ANO’s pledge to raise pensions.

Czechia has been one of Ukraine’s strongest European allies, providing arms, equipment and billions of Czech crowns in aid. Babiš and his potential coalition partners have pledged to scale back that support, raising concerns about a potential shift toward Moscow.

Babiš has downplayed those fears, citing his Agrofert conglomerate’s dependence on EU funds and his opposition to lifting sanctions on Russia.

If Babiš succeeds in forming a government, he will face the challenge of holding together a fragile alliance. Policy differences with SPD and Motoristé sobě could complicate decision-making and stall legislation in the Chamber of Deputies.

Despite the uncertainty, this parliament will be the most gender-diverse in Czech history, with women holding more than one-third of the seats, a sign that even as Czech policy shifts to the right, representation is broadening.